The Day History Refuses to Let Us Forget

By IPS Editorial Board

This month, we acknowledge the historically and culturally significant day of August 28, both the victories and the painful atrocities that shaped our country’s civil rights. On this specific date spanning multiple decades, events uplifted the Civil Rights movement through hope, progress, and, sadly, even despair.

August 28th first secured its mark in history in 1833 when the Slavery Abolition Act ended the practice of slavery in the British colonies. Canada, as a British colony, was also part of this legislation, which made it a free land and refuge for enslaved Black Americans. For many slaves seeking freedom, it was the final terminal on the Underground Railroad, delivering between 30,000 and 40,000 fugitives to British North America.

The next significant event to occur on August 28th was one of violence and despair, but it facilitated one of the most important movements in American history. In 1955, Emmett Till, a young, Black 14-year-old, was brutally murdered in Mississippi for being wrongfully accused of whistling at a white woman. This energized Black leaders and activists, and the Civil Rights Movement was born.

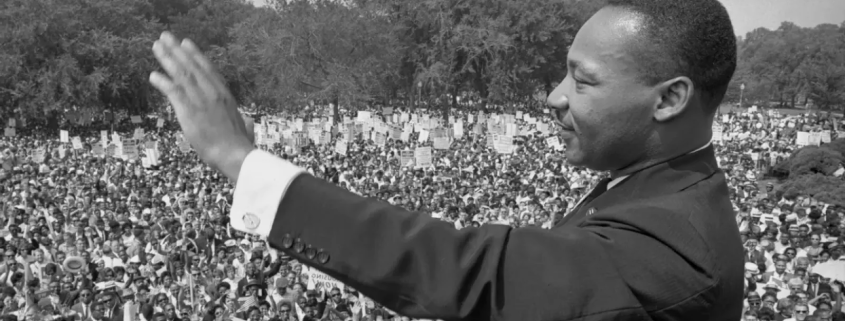

Eight years later, on August 28, 1963, during his March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Dr. Martin Luther King delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech on the Washington Mall. Following his impassioned plea for equality among all people, significant legislation was passed – the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

On August 28, 2008, a young community organizer from Chicago, Barack Obama, accepted the Democratic Party nomination for president, and ultimately became the first African American to hold the highest office in the U.S.

Twelve years later, on August 28, 2020, the death of a young African American actor, Chadwick Boseman, sparked conversations about colon cancer among the Black population and exposed health disparities among minorities.

Preserving Our Collective Memory

What if history books failed to acknowledge these significant events? What if they were whitewashed (at best) or completely erased (at worst) …what does this say about our nation’s collective memory of civil rights? What would society look like today?

The Civil Rights Movement is so ingrained in the fabric of the U.S.’s history and self-reflection on racial reckoning that monuments, museums, documentaries, and the passing of significant legislation are all dedicated to keeping the triumphs, struggles, progress, challenges and injustices equally significant. Some events in its history are cause to celebrate; others require a more painful reflection on the self-serving and shameful nature of human beings.

And yet, the danger of forgetting remains. Recent efforts to erase even the most painful part of our country’s history through executive orders that “remove improper ideology” and “divisive, race-centered ideology” deny present and future generations the ability to acknowledge injustices as one our countries foundational building blocks, painful as they may be, yet equally stacked with all the wonderful and progressive things that make our country great. To deny the hard-fought battles of the civil rights movement is a slap in the face to those who sacrificed everything, including their lives, so that we can live in a society with more dignity, humanity and equity.

If these stories vanish from our collective memory, so does the blueprint for progress. Social justice movements today—from Black Lives Matter to environmental justice coalitions—are informed by the lessons of Selma, Montgomery, Birmingham, and beyond. Without a preserved and honest account of the past, how can we recognize injustice in the present? How can we organize, resist, and reform if we believe that struggle never existed?

Preserving our collective memory is about telling the truth, even when it is uncomfortable. It is about equipping future generations with the moral clarity and historical context they need to confront inequality. Our history—messy, painful, and powerful—must remain visible and vivid, not buried beneath politics or apathy. Because memory is not passive—it is active. It shapes our values, our institutions, and ultimately, our future.