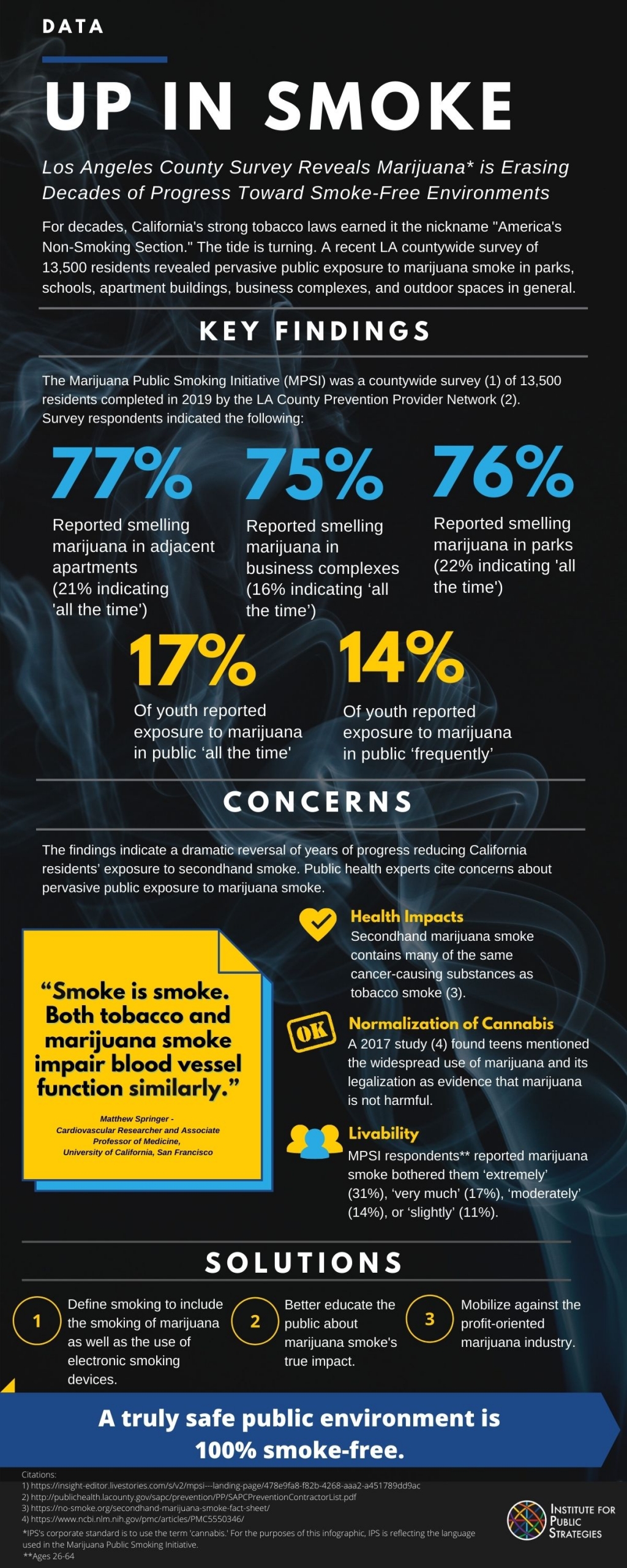

Up in Smoke: Marijuana is Erasing Decades of Progress Toward Smoke-Free Environments

Download ‘Up in Smoke’ Infographic.

A recent Los Angeles countywide survey of 13,500 residents revealed pervasive public exposure to marijuana* smoke in parks, schools, apartment buildings, business complexes and outdoor spaces. Completed in 2019 by the LA County Prevention Provider Network, the survey found, for adults ages 26 and up:

- 77% reported smelling marijuana in adjacent apartments (21% all the time)

- 76% reported smelling marijuana in parks (22% all the time)

- 75% reported smelling marijuana in business complexes (16% all the time)

- 70% reported smelling marijuana in schools.

Youth were no exception. Seventeen percent of youth respondents reported exposure to marijuana in public all the time and 14% reported frequently.

The findings indicate a dramatic reversal to the years of progress that reduced California residents’ exposure to secondhand smoke. Before the legalization of recreational marijuana, California was considered America’s non-smoking section. In 1995, it was the first state to ban smoking tobacco in nearly every workplace and indoor public spaces. In the following years, the ban extended to restaurants, bars, taverns, and gaming clubs.

More recently, in 2016, California enacted multiple tobacco control laws that closed loopholes in the state’s smoke-free laws, including defining e-cigarettes as a tobacco product and prohibiting vaping wherever smoking is not allowed. For decades, the state’s strong tobacco laws were widely considered to have protected people – and youth in particular – from secondhand smoke.

Today, the tide seems to be turning. Public health experts cite two primary concerns about pervasive public exposure to marijuana smoke. For one, research shows that secondhand marijuana smoke contains many of the same cancer-causing substances and toxic chemicals as tobacco smoke and can create harmful cardiovascular health effects, including atherosclerosis, heart attack, and stroke.

“Smoke is smoke. Both tobacco and marijuana smoke impair blood vessel function similarly,” said Matthew Springer, cardiovascular researcher and associate professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

Additionally, the normalization of marijuana smoke could influence youth use. Research shows the more marijuana use is seen as normal, the more likely youth are to try it. A 2014 survey by ABC News Radio found that three times the number of youths whose parents smoked marijuana reported smoking it themselves (72%). Only 20% of youth respondents reported smoking marijuana whose parents didn’t smoke. A 2017 study published in the U.S. National Library of Medicine found that teens mentioned the widespread use of marijuana by people they know and its legalization as evidence that marijuana is not harmful. According to the study, “the findings suggest that normalization of marijuana use is taking place.”

Beyond the public health implications, the LA County survey found marijuana smoke is bothersome. Seventy-three percent of respondents indicated some measure of annoyance, reporting marijuana smoke bothered them extremely (31%), very much (17%), moderately (14%), or slightly (11%).

These issues become more pressing as increasing numbers of states change their marijuana laws. In last month’s election, voters in Arizona, Montana, New Jersey, and South Dakota legalized marijuana for recreational use, joining the 11 states that had already done so. Policymakers in those states could look to California as a bellwether for what’s ahead.

So what can be done about it?

First, if a state legalizes marijuana, state and local jurisdictions should move quickly to define smoking to include the smoking of marijuana as well as the use of electronic smoking devices. New laws must be clear and comprehensive to avoid loopholes. In March 2019, for example, LA County expanded its smoke-free laws by clearly articulating its existing ban on tobacco products at beaches, parks, and government buildings, including electronic cigarettes and marijuana.

Second, the public must be educated on new smoking laws and on the true impact of marijuana smoke. While misinformation about secondhand marijuana smoke abounds, the data in an ever-emerging research landscape makes clear that secondhand marijuana smoke has negative health impacts. Smoke-free laws that include marijuana will better protect workers and the public from all forms of secondhand smoke and vapor.

Third, public health professionals must always be at the ready to push back on the motivated, profit-oriented marijuana industry. According to the Non-Smoker’s Rights Foundation, marijuana industry representatives could use tactics from the tobacco playbook, including loosening terms like “public” in ways more favorable to their purposes of normalizing marijuana use everywhere.

The truth is, a safe public environment is 100% smoke-free. It is possible to return to the clean air gains that were made with a renewed commitment in 2021 – by engaging health partners, the public and legislators at the state, county, and local levels. Let’s get to work.

* IPS’s corporate standard is to use the term ‘cannabis.’ For the purposes of this Hot Topic, IPS is reflecting the language used in the L.A. County Marijuana Public Smoking Initiative.

Author:

Sarah Blanch

Vice President of Organizational Development, IPS

Sarah is responsible for developing and implementing tactical plans that support the vision, mission, goals and growth of the agency. Sarah leads IPS projects in Los Angeles County, where she oversees the implementation of policy-focused initiatives intended to improve public health and safety throughout the City and County of Los Angeles.