Think the census is no big deal? Think again.

While all eyes are on the Democratic National Convention and the official coming out party for Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, let’s not forget about the looming deadline for the 2020 U.S. Census. It will determine how the maps are drawn for redistricting for the House of Representatives and influence the political make-up of Congress in 2022. It could possibly be the most important census ever.

Since the first census in 1790, led by then Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, the decennial census count has been a backbone of our democracy. In addition to accurately helping to divide 435 congressional seats among the states, census results are also used to fairly distribute more than $1.5 trillion in federal funding annually.

This federal funding helps makes up state general fund revenues, including funding for public health programs.

The census is required to count every person residing in the U.S. — citizens, non-citizen legal residents and unauthorized residents. Our democratic process depends on a fair and accurate census count.

The 2020 Census is particularly challenged by the global coronavirus pandemic, threats to undocumented immigrants and their families, political influence in the counting process, as well as security problems with the first largely online census.

Experts fear serious under counts would invite lawsuits that could cripple the reallocation of Congressional seats and redistricting process, as well as drain public trust in this core function of government. Any loss in faith in the census – for any reason — would bring lasting damage.

We must be vigilant to make sure that we obtain as fair and accurate a census count as possible.

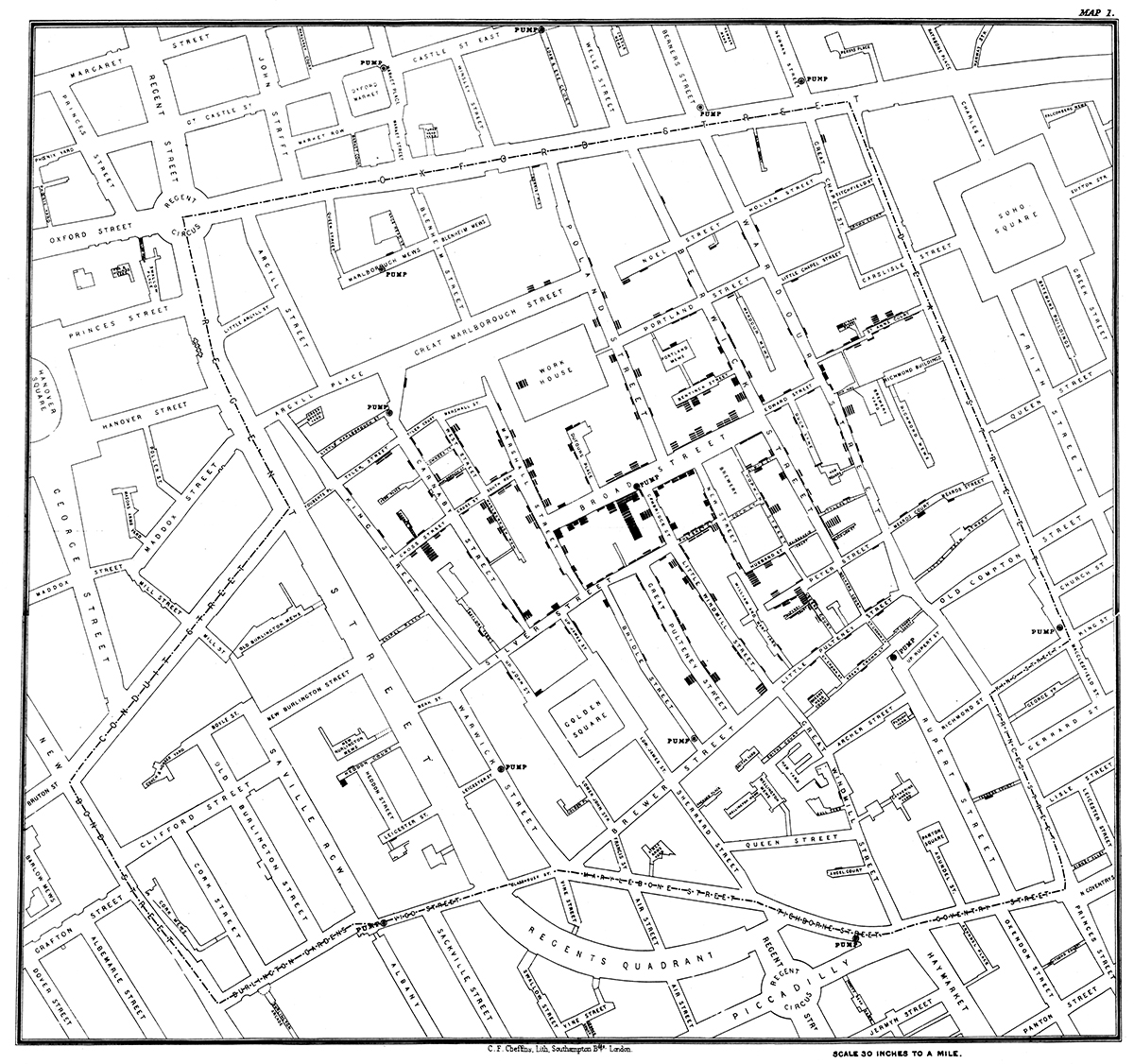

The last census was believed to be most accurate census yet. But while it was accurate, was it fair? The 2010 census was only off by .1%, but hiding in that small overall error were much larger errors miscounting groups of people. Non-Hispanic whites were over counted by almost 1% nationally, while Blacks were under counted by about 2%. Hispanic people were under counted by 1.5% and other groups were under counted even more.

One of the biggest challenges to the current census has been frequent delays to comply with virus protocols. While the COVID-19 pandemic does not seem to hamper online responses, it has caused delays in interviews by phone, and by-mail census efforts — because social distance requirements have limited the number of staff in both. And virus protocols and the concerns about virus exposure among those being surveyed may significantly hamper the in-person survey process.

Two years ago the administration pushed to get a citizenship question added to the census. A coalition of 17 states, Washington, D.C., and six cities filed a lawsuit to block it. The U.S. Supreme Court ultimately disallowed the addition of the question without further information, so it was not included.

After losing that fight, the administration directed the Census Bureau to gather and provide citizenship data. The effort to not only add this question, but to aggressively go after undocumented immigrants has sewn fear in many undocumented residents and their families. This will make it even harder to count minorities that have already been traditionally under counted.

While the Census Bureau has previously been rigidly nonpartisan, it recently announced that is it creating two new top-level positions—both of which are political appointees. This push by the administration is the latest effort raising concerns among civil liberties advocates that is subjugating the census results.

The 2020 census is the first to be conducted largely online, raising new data security challenges. In fact, the Government Accountability Office identified such risks in a 2019 report and demanded the Census Bureau fix “fundamental cloud security deficiencies.” In February of this year, a GAO report called out that while the Bureau had made progress, they still needed to address serious cyber security weaknesses and concerns.

We must act now. The counting deadline has been moved up to the end of September. Let’s not allow that to detract from importance.

We must take swift actions to remedy potential problems with the census and ensuing results.

First, lawmakers should demand the removal of political appointees from the nonpartisan Census Bureau. Such appointments only threaten not only the accuracy and fairness of the census, but undermine public trust in the results and in our government as a whole.

The Census Bureau should undertake advertising campaigns in multiple languages to assure affected populations that no citizenship question will appear on the 2020 Census and that information they provide to the census cannot be used against them.

The government should broadcast its commitment to maintain census confidentiality and put in place stronger safeguards against misuse.

The census is under threat and with it our fair representation in Congress and access to more than $1.5 trillion in federal funding. Compromising the fairness and accuracy of the census or allowing the Bureau to become politicized threatens to undermine our democratic process and institutions, and thereby the trust of and connection with the U.S. public.

We must do whatever we can to ensure the 2020 Census is fair and accurate. The vitality of our country depends upon it.

Author:

Paul Levikow

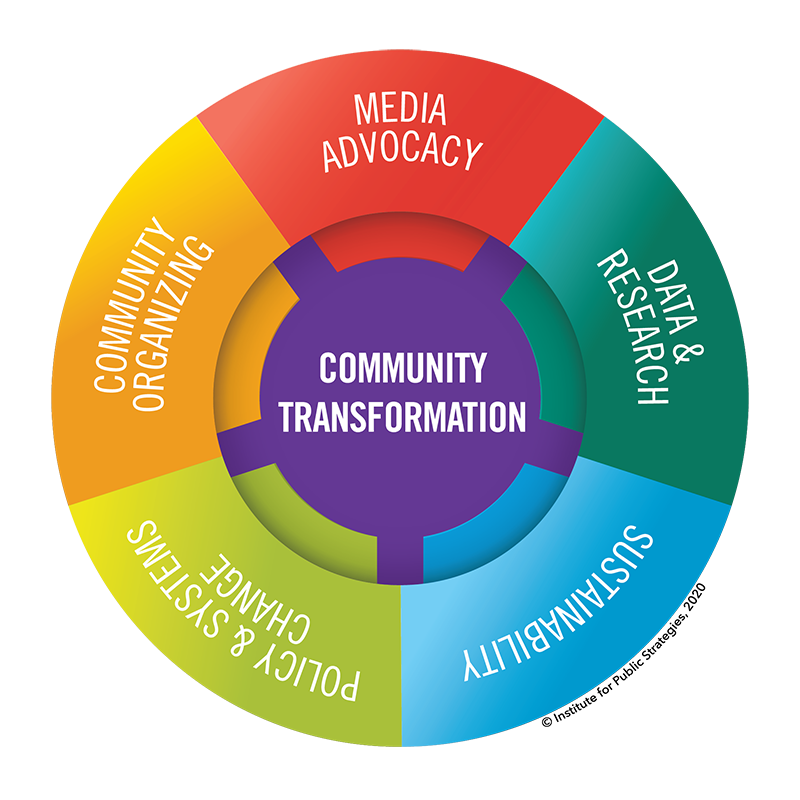

Media Advocacy Specialist, IPS

Paul Levikow is a Media Advocacy Specialist for the East County and South Bay regions in San Diego. Mr. Levikow previously worked for several years as a print and broadcast journalist as well as a communications director and public affairs officer for county government.