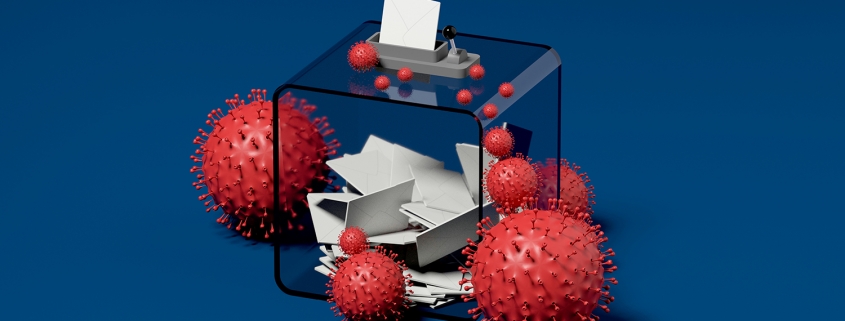

Voters are Being Disenfranchised During COVID. What Can We Do About It?

First, it was images of mailboxes being carted away in pick-up trucks, then states limiting ballot drop boxes to one per county. Now real-time court rulings are changing voting processes and procedures even though voting has already started. All of this is causing alarm, confusion, and hardship. To many, it represents a new tactic from an old playbook – a decades-long practice of suppressing the vote.

Before the 1960s, states often used Jim Crow laws, including literacy tests and poll taxes, to block Blacks, Native Americans, Latinos, and naturalized citizens from voting. While the Voting Rights Act of 1965 brought these practices to an end, deeming them illegal, Barack Obama’s election in 2008 after record voter turnout stirred the pot. By the end of his first term, no less than 27 voter suppression measures were passed or implemented in 19 states.

These measures were the precursor to the 2013 U. S. Supreme Court decision to strike down Section 5 in the Voting Rights Act, opening the door for critical discriminatory practices, including racial gerrymandering. States like Florida took advantage of a weak Voting Rights Act. The legislature passed a law requiring Floridians with a criminal record to pay all fines, fees, and restitution owed in connection with their sentence before being eligible to vote, essentially threatening hundreds of thousands of ex-felons with criminal prosecution if they voted.

These and countless other examples illustrate a pattern of coordinated and intentional efforts to make voting harder – sometimes impossible – for specific segments of the electorate, dating back centuries.

Here in October 2020, we find ourselves at the intersection of two momentous events: a global pandemic and a fraught presidential election. Sadly, the same populations historically targeted by suppression efforts are also disproportionately dying from coronavirus exposure: Blacks, Latinos, and low-income Americans. When voting in person could threaten their very lives, a deadly public health crisis is being leveraged to disenfranchise these same populations. Bringing them into the process means offering ways for all eligible Americans to cast their vote without being forced to travel far or stand in long polling lines.

Logical remedies allow for the full utilization of remote voting options. Despite claims that mail-in ballots lead to fraudulent voting by ineligible individuals, the truth is that this type of fraud is almost nonexistent. An extensive review by Professor Justin Levitt of Loyola Law School found 31 cases of impersonation fraud out of more than 1 billion ballots cast from 2000 to 2014. Still, while wide-spread mail-in ballots are a step in the right direction, voting by mail is threatened by a weakened U.S. Postal Service.

So, now that voting is well underway in most states, what can be done? States must be vigilant and proactive in widely publicizing voting options in simple terms, with clear instructions on voting requirements. Such publicity is even more critical if court rulings result in last-minute changes to voting procedures. Rural and traditionally disenfranchised communities must have easy access to ballot drop boxes. States should provide a system for voters to monitor the receipt and acceptance of their ballot. Communities can support local voting rights groups that are actively engaging in the courts to attempt to stop voter suppression efforts, as was just done in Texas.

And Congress must continue to do whatever it can to support the USPS in the timely and successful delivery of an unprecedented volume of mail-in ballots.

Voting is the cornerstone of our democratic process, and right now, it is no exaggeration to say that the ability of all eligible voters to participate in the November election is under grave threat. During this pandemic, at this moment, we must rise to the challenge. We must learn from history’s lessons. We must bring the vulnerable and disenfranchised into the voting process. Can we? Our democracy depends on it.