Unleashing the Power of Prevention: Looking Forward, Public Policy is the Answer to High Health Care Costs

An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. That statement, submitted by Benjamin Franklin to the citizens of Philadelphia in 1736, was originally a warning to be vigilant about fire prevention. Still relevant after almost 300 years, that timeless phrase has become an American proverb. And its wisdom, it’s fair to say, has been almost universally accepted. Whether it’s speed bumps in a residential neighborhood, routine maintenance on the family car, or the annual medical checkup, prevention has become incorporated into our daily lives.

Another example would be the household fire extinguisher, of which, we can be sure, Ben Franklin would be proud. But Franklin had more than that on his mind when he drafted his essay on prevention for the Pennsylvania Gazette. To be sure, he urged the citizens of Philadelphia to take precautions that would ensure safety in their homes. But he also recommended the adoption of several public policies, measures enacted into law that would protect the entire community. In addition to regulations about the design of hearths, these included the organization of volunteer fire brigades and the licensing of chimney sweeps.

This forward-thinking approach, using public policy to circumvent potential hazards, is still one of our most effective tools to ensure public health and safety. Known as population-level prevention today, it has been successfully applied to many of our most pressing problems. For example, laws making workplaces, restaurants, and bars smoke-free can reduce heart attack hospitalizations by 8–17% according to the Center for Disease Control. And traffic-related fatalities have been significantly reduced over the years though the mandatory use of seat belts along with .08 alcohol consumption laws and DUI enforcement operations.

Controls on alcohol and tobacco products have always been a priority for prevention because they are associated with so many health-related problems. In fact, data show that each of them, along with unhealthy diet and physical inactivity, plays a role in one or more of the top five causes of death in America: cancer, heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and injuries and violence. Of course, in a free society, we can’t compel people to do what’s good for themselves. But we can structure the environment in such a way that there are incentives for adopting healthy behaviors and disincentives for unhealthy ones.

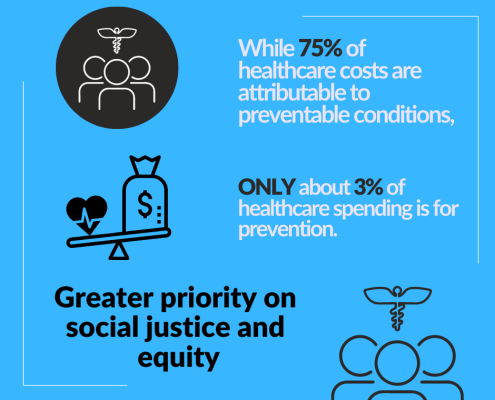

The essence of population-level prevention is going upstream to address the root causes of illness and injury. Such initiatives are usually spurred by the work of nonprofit agencies, mostly with support from state agencies and private foundations. However, despite their success, resources to expand their use, such as funding from the federal government, have been limited. For example, even though 75% of our healthcare costs in America is attributable to preventable conditions, only about 3% of funds is spent on prevention, and most of it comes from states and local municipalities.

The costs involved here are enormous. In 2019, U.S. spending on healthcare – both mental and physical – reached $3.8 trillion, or $11,582 per person. That would amount to about 18% of the nation’s gross domestic product. What’s more, while these expenses have been growing for decades, the percentage spent on prevention has been declining. As such, the reason for the escalating cost of healthcare is not an increase in disease, but our reliance on treatment.

Access to treatment is important, especially for racial and ethnic minorities who have been historically underserved. But we can never expect to hold down the cost of healthcare unless we change our priorities and provide more funding for population-level prevention. More than three-quarters of Americans (76%) support this approach to healthcare reform, according to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Overall, they found that prevention rates higher than providing tax credits to small businesses and prohibiting health insurers from denying coverage based on health status.

But we need to do more than just provide more money. In our work to address the root causes of illness and injury, we need to go even further upstream and consider the context in which they occur. It’s not enough to attribute our problems to the irresponsible behavior of certain individuals. Nor should we rely on singling out the bad actors in the business world who perpetuate them for profit.

But we need to do more than just provide more money. In our work to address the root causes of illness and injury, we need to go even further upstream and consider the context in which they occur. It’s not enough to attribute our problems to the irresponsible behavior of certain individuals. Nor should we rely on singling out the bad actors in the business world who perpetuate them for profit.

These are systemic problems, all of which are interrelated and each of which depends on the others. We may not realize it, but they spring mostly from community conditions like poverty, inadequate housing, availability of healthy foods, racism, crime, and violence. That’s why the status of a person’s health depends largely on their zip code, which makes it clear where our prevention dollars should be spent.

In the final analysis, we’ve only scratched the surface in our prevention efforts. It’s time we go deeper and make the investment that’s required to meet the challenges we face.

Author:

Dan Skiles

Consultant, IPS

Dan Skiles is a consultant and former Executive Director at the Institute for Public Strategies, a Southern California-based nonprofit that works alongside communities to build power, challenge systems of inequity, protect health, and improve quality of life.