Taxing Alcohol to Protect Public Health and Safety Is a Good Thing

Most people cringe at the idea of paying more taxes, including on alcoholic products. But when weighed against the cost that alcohol puts on communities, healthcare, and society, a strong case exists that more taxing is necessary.

An alcohol tax is a type of excise tax that is applied to beer, wine and spirits at the time of purchase. Generally, these taxes are implemented for two purposes. First, the financial benefit to taxing the sales of controlled substances is obvious. As demonstrated through historically high sales of alcohol leading into and following the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as historical state revenue from these measures, taxes on controlled substances can represent a significant proportion of total tax dollars going to the state—despite making up a small percentage of total taxes.

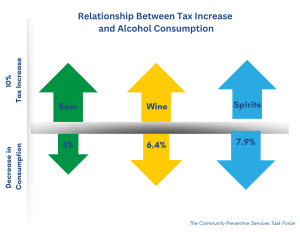

Second, these taxes are intended to have a preventative effect on substance use by disincentivizing drinking—especially excessive drinking. As one of the major causes of acute and chronic disease and illnesses, alcohol consumption is a key concern for state public health officials by placing a tremendous financial and material strain on healthcare, emergency responders, and social services, as well as adjudication and workplace productivity costs. These costs are broadly passed on to residents and community members.

Rather than keeping up with the rising costs to public health and safety of alcohol, taxes on alcohol are either remaining stagnant or even being lowered. Essentially, alcohol is a commodity that generates $10.2 billion in revenue from taxes, yet results in a loss of $249 billion in costs to society. The disparity is stark.

Despite many states’ goals to reduce excessive and life-threatening alcohol consumption, several still fail to fully utilize taxes as a public health tool. California, for instance, languishes behind many other states in its alcohol excise taxes, charging pennies on the dollar for the sales of distilled spirits when viewed alongside comparable geographies—as much as ten times less than other states like Washington and Oregon.

One step that some states can take is to change regulations regarding alcohol taxation. One specific example is to categorize “alcopops”—pre-mixed boozy beverages like Four Loko and Mountain Dew Hard—as distilled spirits rather than malt beverages. This puts their sales prices much higher and is hypothesized to present a greater barrier to purchase, specifically for youths at risk of being enticed by marketing and packaging.

Increasing numbers of community members, prevention specialists, and lawmakers are understanding the damage alcohol causes and leading advocacy efforts to raise alcohol taxes. States like Illinois and Maryland, for example, have taken bold steps to increase alcohol taxes and have seen dramatic reductions in impaired driving and fatal alcohol-related motor vehicle crashes. It’s a steep climb for advocates of alcohol harm prevention to reverse decades of stagnant tax policy, but the benefits of increasing excise taxes on alcohol will become apparent to communities when issues like calls for police service, DUI crashes, and other alcohol-related harms are reduced.

For the families of the hundreds of thousands of men, women, and children who die each year from alcohol-related harms, it’s past time for lawmakers to acknowledge that alcohol excise tax rates and the public health costs of alcohol are dramatically out of alignment.

Author:

Michael Pesavento

Communications Specialist

Michael Pesavento is a Communications Specialist in the San Diego County office. He serves on the Binge and Underage Drinking Initiative that aims to reduce harms and responsibly regulate drug and alcohol usage in the San Diego area.