A Perfect Storm: When Climate Change, Racial Justice, and Mental Health Collide

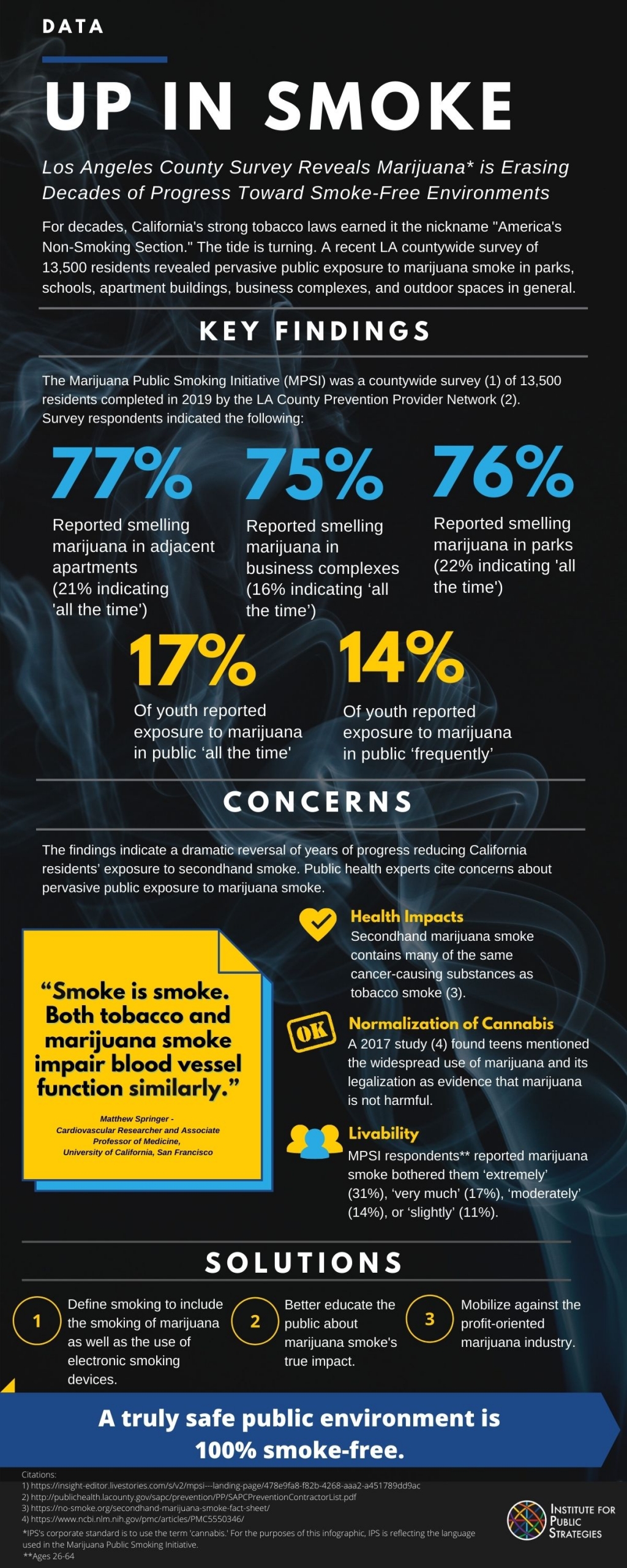

April is a busy month for mental health awareness: National Minority Health Month, Alcohol Awareness Month, and Stress Awareness Month. When you add in Earth Day, this is a good time to remember that stewardship of the planet goes hand in hand with safeguarding mental health. After all, clean air and water, safe neighborhoods, and intact social networks are part of the social determinants of health. But when they are compromised or destroyed by Mother Nature, it can cripple a community’s ability to cope. This can lead to stress, anxiety, depression, and self-medication through substance use.

Communities of color are most vulnerable to the effects of the 21st century’s biggest challenge – climate change. With fewer resources and systemic racism in post-disaster recovery, they disproportionately suffer from injustices brought on by droughts, intense storms, destructive wildfires, and catastrophic flooding.

Environmental Justice is Racial Justice

Junee Kim knows this all too well. She is a high school student in Montgomery County, MD, and a climate activist with the BIPOC Green New Deal Internship program.

“One of our environmental goals is to hold the school district accountable to their commitment to electric buses, but they have drifted away from that by buying more diesel ones,” said Junee, a sophomore at Watkins Mill High School in Gaithersburg, MD. “I’m worried for my generation and the ones after us,” she said. “Many of my peers are stressed about climate change, but there isn’t a whole lot of awareness of how climate change impacts mental health and how to deal with it.”

Junee describes climate change as especially scary for underprivileged people and people of color because they are the ones most affected. “Not only will Earth deteriorate, but the gap between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots’ will continue to widen.”

If there was one silver lining brought on by Hurricane Katrina in 2005, it was the urgency to address the racial disparities and social injustice brought on by climate change and natural disasters. Research continues to show that non-white neighborhoods are more likely to be impacted by flooding, as experienced by Black and Hispanic communities during Katrina and later by Hurricane Harvey in 2017.

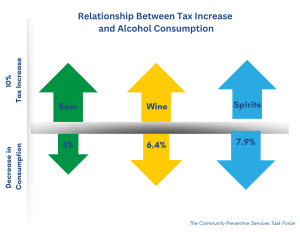

Elevated temperatures from global warming also highlight the struggles of low-income, inner-city neighborhoods, which are mostly inhabited by people of color. These areas are often trapped in “heat islands” where temperatures are much higher than surrounding areas with more green space. Residents of these neighborhoods are less likely to have an air-conditioner or a car that they can take to a “cool zone” compared to a predominantly white neighborhood. Exposure to such intense heat increases the risk of heat stroke, heat exhaustion, and heart attacks. Alcohol, drugs, and heat just don’t mix. They exasperate the underlying physical conditions or lead to new ones.

The Intersection of Climate Change, Mental Health, and Substance Misuse

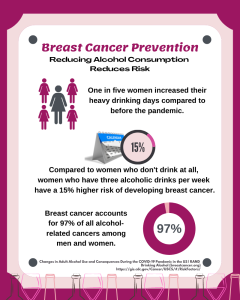

The trauma caused by Katrina caused many of the displaced disaster victims – mostly Black – to turn to substance use. In Houston, one in four Blacks said their mental health had gotten worse and 11% of Blacks report they increased their alcohol use as a result of Harvey.

The West Coast doesn’t fare much better with its climate challenges. In California, devastating wildfires resulted in an uptick in prescription pill use. Researchers from Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health recently found that hospital visits from alcohol and drugs increased as a result of rising temperatures due to climate change.

Policy Responses and Adaptation Strategies

Because climate change is a complex and divisive issue, solutions can be equally perplexing. It requires a multi-faceted approach that integrates public health, social justice, and environmental science and technology. Most importantly, it must be community-driven, with those most impacted having a seat at the table.

One crucial aspect of a policy response is to be proactive rather than reactive. This means prioritizing interventions that promote community resiliency in under-resourced neighborhoods and communities of color, both in terms of physical infrastructure and mental health by doing the following:

- Prioritize households with residents who are low-income, elderly, disabled, or non-English speaking in evacuation plans.

- Demystify the process of receiving post-disaster aid by increasing the health and financial literacy of community members.

- Establish mental health services and community support systems well in advance of natural disasters that equip individuals with healthy coping mechanisms that do not involve substance use.

- Incorporate programs into high schools that foster advocacy and build resiliency, such as a resident leadership academy or Mind Matters.

- Build a network of ‘trusted messengers’ – the people who carry out public health strategies within their communities.

“The first step is just understanding the effects climate change has on mental health,” according to Junee. “And only then can we address the resiliency part.”

Author:

Meredith Gibson

Media/GIS Director, IPS

Meredith Gibson is the Media/GIS Director at the Institute for Public Strategies. She uses geographic information systems (GIS) and media advocacy to promote systems and policy changes that contribute to healthy, safe, vibrant, and equitable communities.